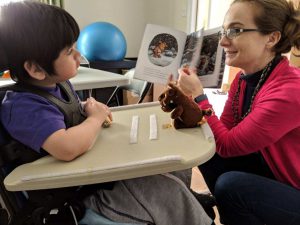

Without his device, Joey has been choosing to read books that give him more opportunities to interact during the read aloud. He wants to hold an animal, wave a magic wand, or move a velcroed piece around on his work tray. Last week I wondered just what was so appealing about Room on the Broom that we couldn’t break away from reading it. Through looking at what the Room on the Broom read aloud structure looks like for Joey, and considering that without his device read alouds can be more of a listening experience than an interactive one, I realized I needed to increase the opportunities for Joey to engage during a book. [Read more…]

Without his device, Joey has been choosing to read books that give him more opportunities to interact during the read aloud. He wants to hold an animal, wave a magic wand, or move a velcroed piece around on his work tray. Last week I wondered just what was so appealing about Room on the Broom that we couldn’t break away from reading it. Through looking at what the Room on the Broom read aloud structure looks like for Joey, and considering that without his device read alouds can be more of a listening experience than an interactive one, I realized I needed to increase the opportunities for Joey to engage during a book. [Read more…]

What Makes a Good Book for Joey?

I’m not sure what I’ll do if I have to read Room on the Broom one more time with Joey (OK, truthfully we all know that I’ll read it and be as excited about reading it as I was the first time…) but I honestly am not sure I can. I’ve stretched the book as far as I can. We’ve counted characters forwards and backwards, identified rhyming words, acted it out, spent time on the prepositions of the book, talked about weather, emotions, and even friendship. Yet still, Joey latches onto it. [Read more…]

I’m not sure what I’ll do if I have to read Room on the Broom one more time with Joey (OK, truthfully we all know that I’ll read it and be as excited about reading it as I was the first time…) but I honestly am not sure I can. I’ve stretched the book as far as I can. We’ve counted characters forwards and backwards, identified rhyming words, acted it out, spent time on the prepositions of the book, talked about weather, emotions, and even friendship. Yet still, Joey latches onto it. [Read more…]

Giggles

“What comes next?” I asked Joey, holding up the 5 and the 14 number cards. We’d just put down four and were building a long number line. Joey looked me in the eyes, then promptly looked at the number 14. And then burst into a fit of giggles.

“What comes next?” I asked Joey, holding up the 5 and the 14 number cards. We’d just put down four and were building a long number line. Joey looked me in the eyes, then promptly looked at the number 14. And then burst into a fit of giggles.

Right. The kid knew exactly what he was doing.

“14? 3, 4, 14? Is that how we count?” I acted huffy. “NO… it’s five!”

Joey looked solemn as I handed him the five and together we added it to the number line we were building. He remained calm as we counted the numbers we already had, touching each one to make sure we had one to one correspondence. [Read more…]

Thinking Vocabulary and Theory of Mind

Every time I see Joey these days he seems to have more words on his device. His vocabulary is exploding, and he spends most of his time exploring these new words. During these times it is always hard for me to track his meaning and determine if he is exploring where his words are, trying to communicate a message, or if he is unintentionally hitting the new words while seeking out the old ones. I’ve learned to sit back and listen to him and give meaning to his words when I can.

Every time I see Joey these days he seems to have more words on his device. His vocabulary is exploding, and he spends most of his time exploring these new words. During these times it is always hard for me to track his meaning and determine if he is exploring where his words are, trying to communicate a message, or if he is unintentionally hitting the new words while seeking out the old ones. I’ve learned to sit back and listen to him and give meaning to his words when I can.

In the most recent set of words, Joey gained the ability to communicate the idea of thought with the words think, thinks, thinking, and idea. It surprised me how much deeper he was able to communicate once he could add these words to his thoughts. [Read more…]

Turning the Tables

In my ongoing work with Joey I’ve learned that he doesn’t like to be prompted to use particular words. If I prompt him to use want, he’ll use every word BUT want, or will refuse to talk to me. It’s taken me awhile, but I’ve eventually learned to use more naturalistic methods and to accept Joey’s total communication, instead of demanding him to use the words I choose. [Read more…]

In my ongoing work with Joey I’ve learned that he doesn’t like to be prompted to use particular words. If I prompt him to use want, he’ll use every word BUT want, or will refuse to talk to me. It’s taken me awhile, but I’ve eventually learned to use more naturalistic methods and to accept Joey’s total communication, instead of demanding him to use the words I choose. [Read more…]

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- Next Page »