So often, people who use AAC to communicate find themselves caught in the ability to only communicate with those who understand how AAC devices work in situations where AAC devices are available. It can be a small world in which to communicate. And yet, those of us who are able-bodied are only currently able-bodied. It is not something any of us want to think about, but any of us are capable of one day relying on AAC supports in order to reach the world around us.

So often, people who use AAC to communicate find themselves caught in the ability to only communicate with those who understand how AAC devices work in situations where AAC devices are available. It can be a small world in which to communicate. And yet, those of us who are able-bodied are only currently able-bodied. It is not something any of us want to think about, but any of us are capable of one day relying on AAC supports in order to reach the world around us.

Somewhere in my quarantined on-line searches I stumbled upon this resource page from the Patient-Provider Communication Forum. The resources were developed by speech-language pathologists, nursing leaders, engineers, and with help from the U.S. Society of Augmentative and Alternative Communications. It provides pages of low-tech pictures that can be provided to people with COVID-19 who are unable to communicate.

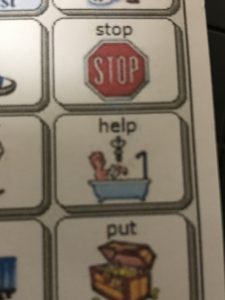

I got caught up in reading through the boards, looking for the similarities and differences between these medical boards and the daily core vocabulary we use with students. In this case, the core vocabulary and stock phrases need to be specific – they are not preparing a person to use this device to communicate with the greater world – they are using this specific vocabulary to allow an individual to connect, communicate, and self-advocate in a time of medical necessity.

The words identified that are essential “core vocabulary” for those communicating with healthcare professionals in order to have their basic needs met include a pain scale, a Yes/No/Maybe board, and a list of potential requests someone may make – anything from what time or day it is to the need for suction, the bathroom, or to request no visitors. The tools come with specific pages that teach the medical team how to use the boards in order to ensure a correct interpretation of the patient’s request.

One board includes a list of specific medical questions.

“When will I get better?”

What are my options?

When will I be off the ventilator?

Am I going to die?

I want my family to decide.

The pediatric board includes phrases like “leave me alone”, which is much more to the point than the polite “no visitors” request on the adult board. “Hold my hand” is another choice on the board, which I am sure is essential for both children and adults – the need to be connected and near with one another.

The site also provides directions on preparing the boards, tips and tricks, and case samples.

I felt so many emotions roll over me as I went through the site. It is a bit shocking to see the picture symbols of the scary questions we want answered by a doctor, and threatening to think that to ask our most desperate questions we have to borrow someone else’s pre-printed words in order to do so. It is also sobering to realize that on top of everything else, health care providers are learning how to use AAC. Yet the emotion that seemed to sit with me the longest was a mixture of thankfulness and hope. I am so thankful for the team that put this together, and that doctors, nurses, and other providers are taking the time to use these resources. Of course, I wish I didn’t have to, but the resources’ existence in itself is a symbol of how we are honoring people’s individuality and humanity when they need it the most. And of course, hope that these lessons stay with us all, and that we appreciate that the power of speech is not connected with our intelligence, and that the need to use AAC, either in a low tech or high-tech form, is not a sign of weakness or limitations. Instead, it represents the power of one’s self and the human need to express opinions, make requests, and ask questions to connect.