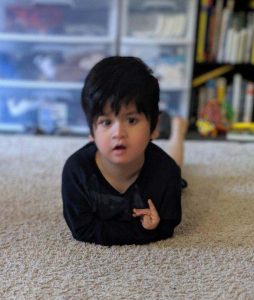

One day I came in for a session with Joey and it felt as though I was engaging with another student. He couldn’t take his eyes off his screen, and rapidly fired words at me over and over again. If the words were connected I couldn’t follow his message, and if he asked me questions he did not wait for a response. It was so unlike him and I couldn’t stop wondering what was going on.

One day I came in for a session with Joey and it felt as though I was engaging with another student. He couldn’t take his eyes off his screen, and rapidly fired words at me over and over again. If the words were connected I couldn’t follow his message, and if he asked me questions he did not wait for a response. It was so unlike him and I couldn’t stop wondering what was going on.

I kept trying to get his attention, slow him down, and ask him to pause and look at me, but he wouldn’t – word after word spurted out of the device – so quickly that I couldn’t even collect my traditional data. What was happening here? I heard this is what he was doing in school as well, and I started to question everything I’ve ever done with Joey. Was he really able to use his device to speak, or was it all just coincidence until he gained this rapid fire ability and now he just strung words together, showing us he never understood anything to begin with?

At one of my recent presentations on our research around Joey’s use of the AAC, a member of the audience approached me after I finished. He politely explained to me that the term “presume competence” was being abused by AAC representatives trying to sell devices, and that the field was trying to not use it anymore. “Presume potential” is what I should use instead. “Presume potential doesn’t seem to quite fit my work with Joey – I will presume he has the ability one day, but not right now? But if I do make that decision, presume the potential – then I’m not honoring his communication attempts in real time. But maybe I shouldn’t be? Maybe everything I’ve seen has been a figment of my hopefulness.

Between the questioner and Joey’s sudden change, I was lost. Maybe I haven’t been seeing reality.

While I worked on slowing down Joey’s rhythm and working on his back and forth “serve and return” interactions, I also asked the family to check the response time of the device. We’d recently talked about speeding it up to make it easier for him. Maybe he couldn’t handle this increased speed. Knowing they had only increased it by the smallest amount, I didn’t think this should make a difference. But maybe?

After about three sessions of Joey’s fast paced and limited interactions I returned to his house to hear that they had checked the device. It had somehow gotten sped up to almost full speed – meaning that any time Joey’s eyes glanced at a word the device would say the word. It had not been Joey’s problem that was creating the rapid fire words – it was the device all along. Usually, it always is. I don’t know why I question it.

They also added a new setting on the device – a cursor that will follow Joey’s eye gaze. It shows us just where he is looking – and how difficult it is for him to set his eyes on one specific icon. It’s excruciating to watch his determination, and yet, he does not give up – coming back time and time again for the right word.

I do think it is important to always question ourselves and our perspectives as teachers and therapists, and always be ready to ask “am I seeing what is there, or seeing what I want to see?” But at the same time, Joey has once again reminded me the importance of presuming competence. Joey wasn’t broken – he was trying to communicate a message while the device no longer responded to him in a comfortable way. And all the while those of us around him acted as though it was his problem.

As far as the term of presuming competence – I don’t know about what war is going on with the term, or what terminology I “should” use. What I do know is that those two words remind me to presume Joey’s capabilities in the moment. I am going to continue to use the words that make me a better teacher in the moment – and think deeper not about what could be one day, but what I just might not be seeing right now.