I found myself getting nervous before my opportunity to present the research on Joey’s progress at the Council for Exceptional Children’s DADD conference in January. Joey’s journey is unique, but as I scrolled through my prepared slides I wondered if I was on the right track. So much of my work with Joey has involved throwing off what I was taught in terms of behavioral approaches and meeting Joey where he asks to be met. Not what I plan for Joey to do, or what I’ve done with students in the past, but where Joey shows me he is ready to work. Although this is the right approach for Joey, and I truly believe in the approaches we take for him, I realized I was nervous about the response I would get. Sometimes it just feels too different than the otherwise straightforward approaches to teaching communication. The audience of this conference included many doctoral degrees and experts in the field. What if I was doing everything wrong, and everyone heard me say it aloud?

I found myself getting nervous before my opportunity to present the research on Joey’s progress at the Council for Exceptional Children’s DADD conference in January. Joey’s journey is unique, but as I scrolled through my prepared slides I wondered if I was on the right track. So much of my work with Joey has involved throwing off what I was taught in terms of behavioral approaches and meeting Joey where he asks to be met. Not what I plan for Joey to do, or what I’ve done with students in the past, but where Joey shows me he is ready to work. Although this is the right approach for Joey, and I truly believe in the approaches we take for him, I realized I was nervous about the response I would get. Sometimes it just feels too different than the otherwise straightforward approaches to teaching communication. The audience of this conference included many doctoral degrees and experts in the field. What if I was doing everything wrong, and everyone heard me say it aloud?

Quickly into the presentation, as I was introducing Joey’s early communication patterns, someone audibly gasped. “He had joint attention?” they called out, as I was describing how Joey initiated having a demand met by locking eyes with someone and then looking around in the room to show what he wants. “That’s so hard to achieve!” It was then I was able to remind myself that Joey is unique. This is where he differs from our expectations.

But what if Joey isn’t that different?

So often we make assumptions about children’s ability to communicate simply because they do not speak words themselves. We assume they do not have joint or shared attention, and assume they need to be taught this step before moving on. And some children do not have this foundational skill yet, and need to develop this before moving forward. Yet if we make that assumption without first observing the child’s strengths, we force the child backwards, and use teaching techniques that don’t support the child’s growth. Joey, with all his strengths, was able to show me loud and clear what he thought of those types of teaching techniques. I’m glad I was able to listen.

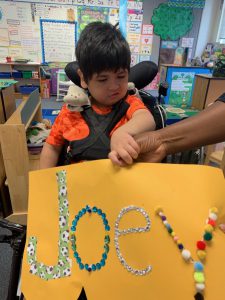

Putting together the presentation, I realized that Joey’s story is one of presuming competence at every stage. We initially made progress with the eye gaze when we began honoring his total communication approaches – recognizing the intent behind his pointing, eye gaze, and gestures, not just forcing him to use his device. We were able to create buy-in for the device only after we paired it by first acknowledging that we saw him and what he wanted, and then showing him how he could use the device to do the same thing. We presume competence when we honor his miscues, and recognize how hard he is working to select each word, even when he continues to hit the wrong picture. In order to teach Joey to read we must presume competence at each step – knowing that he is able to learn to read, and recognizing just how difficult each step will be for him. It is not that he isn’t capable, it is that we don’t yet have an ability to easily support the skills he needs to practice. But we’ll keep working, and so will he.