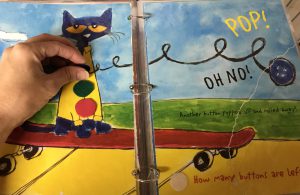

Joey is your definition of a book lover. When he sees a book, his face lights up. When a book ends, he often cries. He is perfectly happy having a book be read to him over and over (and over and over). I am sure anyone in his family can recite Pete the Cat or Little Blue Truck in their sleep. Joey’s love of books works out quite well, as I love books almost as much as Joey, and I particularly love adapting books so they are more accessible, engaging, and powerful for children with special needs.

Joey is your definition of a book lover. When he sees a book, his face lights up. When a book ends, he often cries. He is perfectly happy having a book be read to him over and over (and over and over). I am sure anyone in his family can recite Pete the Cat or Little Blue Truck in their sleep. Joey’s love of books works out quite well, as I love books almost as much as Joey, and I particularly love adapting books so they are more accessible, engaging, and powerful for children with special needs.

I have always thought that books can be magic for many children. They allow children to explore new worlds, meet new characters, and talk about new ideas. They also expose children to new vocabulary, ideas, and language. More importantly, stories have the ability to create a meaningful, positive experience between a parent and child, or a teacher and student. For children who may have difficulty connecting with adults, a book provides a safe, socially acceptable way to interact with a loved adult, without pressure to socially perform.

Throughout my career I’ve met many well-meaning parents of children with special needs who find it difficult to use read alouds as they would with a neuro-typical child. They share that children have difficulty sitting for a read aloud, while others may reach out, grab, and rip the pages. Some simply do not have the expressive language to respond to the book, making those around the child suspect the child is not internalizing the read aloud.

Yet, read alouds offer a great possibility for children, if we are thoughtful about the books we choose, how we present the books, and simple changes we can make in the books to make them more interactive or personalized.

Joey loves books, so meeting his attention span has not been a concern for us. Instead, we have been able to capitalize on this love of books to work on his other goals, such as teaching and reinforcing how to use his eye gaze Augmented Alternative Communication (AAC) device, increasing his core vocabulary and receptive language, providing him opportunities for motor planning, and exposing him to the academic skills he would be learning in a preschool for typically developing children.